Title: The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

Subtitle: N/A

Author: Rebecca Skloot

Other Contributors: N/A

Subject: Henrietta Lacks, Biopolitics, The HeLa cell line, Medical Consent, Racialised Medical Care, Racial Politics, Bodily Autonomy, Consent

Publisher: Crown Publishing Group

Published: 2010

ISBN/DOI/EISBN: 978-1-4000-5217-2

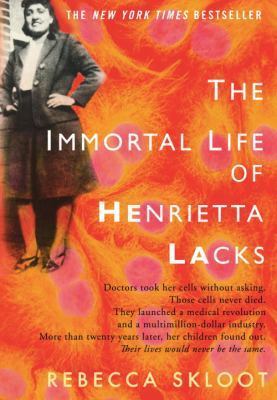

[ID: A book cover. The background is orange, designed to look like human cells under a microscope. Down the upper left side, a black and white photograph of Henrietta Lacks. She is a black woman, is smiling, and wearing a long pleated skirt and long sleeved blazer. To the right of her head, at the top of the cover, text reads “The New York Times Bestseller” in small white capitals.

The title “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks” is written in large white capitals centre right of the cover. “He” and “La” are written in bold.

Directly below this, smaller black text reads: “Doctors took her cells without asking. Those cells never died. They launched a medical revolution and a multimillion-dollar industry. More than twenty years later, her children found out. Their lives would never be the same.” The last line is italicised.

The author’s name “Rebecca Skloot” is written in large white capitals and the bottom of the cover. /end]

Content Notes:

- Cancer

- Terminal Illness

- Medical Trauma

- Issues of Consent

- Forced Institutionalisation

- Death

- Racism

- Child Death

- Abuse

- Incest

- Infidelity

- Medical Content

Summary:

Her name was Henrietta Lacks, but scientists know her as HeLa. She was a poor Southern tobacco farmer who worked the same land as her enslaved ancestors, yet her cells—taken without her knowledge—became one of the most important tools in medicine. The first “immortal” human cells grown in culture, they are still alive today, though she has been dead for more than sixty years. If you could pile all HeLa cells ever grown onto a scale, they’d weigh more than 50 million metric tons—as much as a hundred Empire State Buildings. HeLa cells were vital for developing the polio vaccine; uncovered secrets of cancer, viruses, and the atom bomb’s effects; helped lead to important advances like in vitro fertilization, cloning, and gene mapping; and have been bought and sold by the billions.

Yet Henrietta Lacks remains virtually unknown, buried in an unmarked grave.

Now Rebecca Skloot takes us on an extraordinary journey, from the “colored” ward of Johns Hopkins Hospital in the 1950s to stark white laboratories with freezers full of HeLa cells; from Henrietta’s small, dying hometown of Clover, Virginia — a land of wooden quarters for enslaved people, faith healings, and voodoo — to East Baltimore today, where her children and grandchildren live and struggle with the legacy of her cells.

Henrietta’s family did not learn of her “immortality” until more than twenty years after her death, when scientists investigating HeLa began using her husband and children in research without informed consent. And though the cells had launched a multimillion-dollar industry that sells human biological materials, her family never saw any of the profits. As Rebecca Skloot so brilliantly shows, the story of the Lacks family — past and present — is inextricably connected to the history of experimentation on African Americans, the birth of bioethics, and the legal battles over whether we control the stuff we are made of.

Over the decade it took to uncover this story, Rebecca became enmeshed in the lives of the Lacks family—especially Henrietta’s daughter Deborah, who was devastated to learn about her mother’s cells. She was consumed with questions: Had scientists cloned her mother? Did it hurt her when researchers infected her cells with viruses and shot them into space? What happened to her sister, Elsie, who died in a mental institution at the age of fifteen? And if her mother was so important to medicine, why couldn’t her children afford health insurance?

Intimate in feeling, astonishing in scope, and impossible to put down, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks captures the beauty and drama of scientific discovery, as well as its human consequences.

Notes:

Henrietta Lacks was a black woman whom, at the age of 31, died of cervical cancer in a segregated ward of John Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, 1951. Cells that were taken from her would go on to form the HeLa cell line, the first “immortal” cell line in history, and have contributed towards many great scientific developments and studies, including Covid studies, cancer research, genome mapping etc. etc. The list goes on.

These cells were taken without the consent and/or knowledge of Lacks and her family.

Henrietta’s cells have gone on to revolutionise the world of medicine and science as we know it. Her family received no compensation as biomedical companies profited on these discoveries.

I did read that they filed a lawsuit in 2021 that was settled recently- July 2023- but for an undisclosed amount.

Archivist Comments:

I studied this book for my course. Think I even wrote an essay on it. It was my first proper introduction to the idea of biopolitics.

I have a bit of an issue with the way the author writes herself at times, but I still think this is an important and well written read nonetheless.

This is a link to the Henrietta Lacks Foundation.

Leave a comment